John Paul Brammer, the writer behind the beloved advice column ¡Hola Papi!, is “not a very good advice columnist,” he says. “I don’t say anything concrete in a column like, ‘Oh, you need to break up with him,’” Brammer tells Refinery29. “Instead, I like dwelling in the tough questions.”

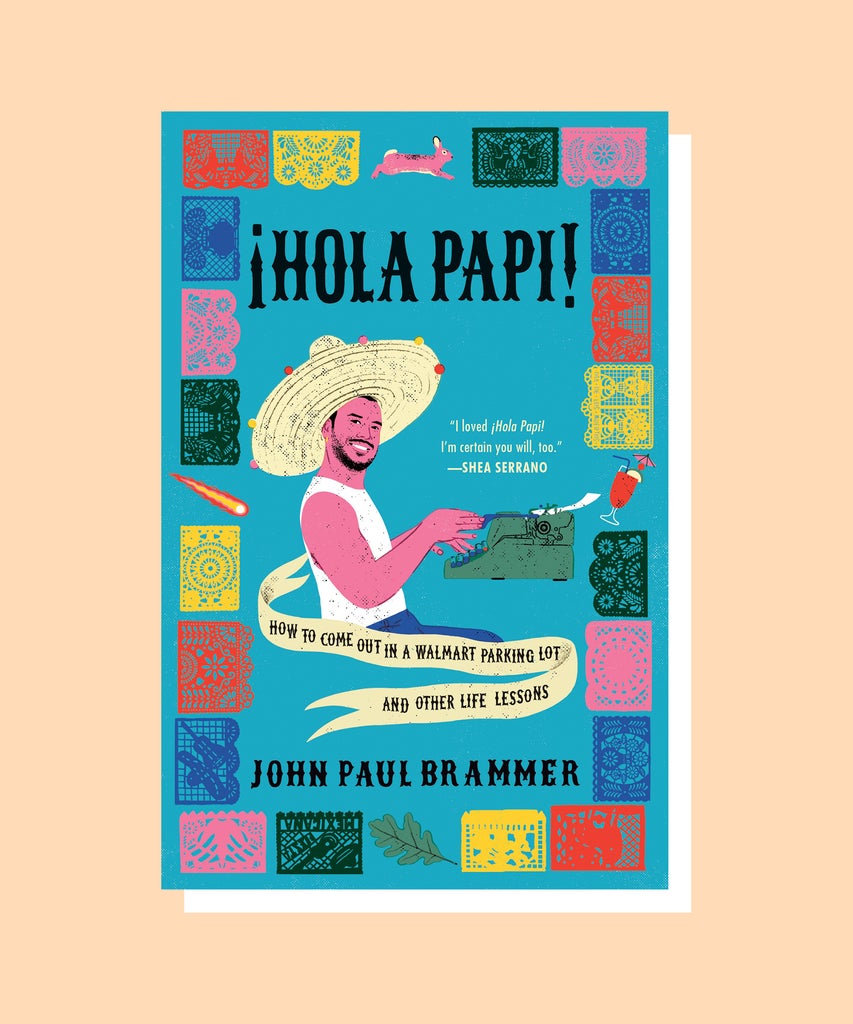

It’s not your typical Dear Abby strategy, but it seems to be working: About four years after the column first appeared in the dating app Grindr’s digital magazine INTO, each new installment of ¡Hola Papi!, which now lives on Substack (and is syndicated weekly by The Cut), lands in 11.5K inboxes. And now, Brammer has published a book: ¡Hola Papi! — How To Come Out In a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons, which was released today. It isn’t quite self-help, but reading it feels a lot like going to therapy — if the therapist was also your funniest friend. As in his column, Brammer’s prose in the memoir-in-essays is notably witty and deeply personal. Yet, it’s themes are universal: trauma, identity, heartbreak, and the stories we tell about ourselves.

Speaking with Refinery29 over Zoom, Brammer opens up about being an anti-advice-column advice columnist — and why he thinks no one (besides “a doctor or Dolly Parton”) is truly qualified to give advice.

Refinery29: The advice you give in your column, ¡Hola Papi!, always strikes me as incredibly thoughtful, honest, and wise. So I was interested by the sections of your book where you talked about feeling unqualified to answer certain questions. Tell me more about how you know when it’s appropriate for you to give advice, or what advice is appropriate for you to give.

John Paul Brammer: “I originally intended ¡Hola Papi! to be a satire on other advice columns. The punchline was that I, this nobody random gay Mexican guy living in New York, was going to tell other people how to live. Then when the letters started coming in and they were very serious and thoughtful. I decided, ‘Oh God, now I have to actually be an advice columnist.’ So the central conflict of the book is being put in a situation where you have authority and a responsibility to other people, but you’re not quite ready to meet that obligation. What I love about the book is that it actually begins and ends with me not answering a letter because I thought answering it could do more harm than good.”

Yes. The letter was from a man living in a country where being queer was illegal, and he was attracted to someone at work, and wondering if he should make a move.

“Right. And I decide not to answer it. Over several chapters, I’m recounting my credentials. I’m saying, ‘See, all these things happen, and I overcame them. I learned lessons.’ And then at the end, I’m saying, ‘All that actually doesn’t cohere into wisdom that I can give in this particular instance.’ It’s about knowing, ‘Where am I helpful? Where am I not helpful? What do I know? What do I not know?’

“For example, I talk about being bullied, being abused, being attacked for being perceived as gay in middle school. The main visual in that chapter is me sitting by a wall, and I can see the shape of a rabbit in the wall in the pebbles. Then you see me going on in life and trying to push myself really hard to be a success story; trying to have the nice job, live in New York, have a successful advice column. And then visiting that school again, trying to see all the things I saw when I was young [and] vulnerable, and realizing that my idea of this school had been in my mind this whole time. For so long, I felt I needed to make sure that what happened to me at that school never happened to me again. And then after all that, I come back and I can’t see the same thing as I saw before — I can’t see the rabbit in the wall. The stories we tell ourselves are unreliable, but they can give us a degree of agency. We can tell the story a different way, and that can maybe help us live more productive, happier lives.”

That was a beautiful chapter. I was especially touched by this line: “Trauma is always trying to convince us that we are beings trapped in amber, defined by the static, unchangeable events of our lives. But that’s not the case. The worst things that have ever happened to us, don’t define us. We are the ones who get to define what those things mean.”

“One thing that I was really obsessed with — you can tell because it’s a connecting thread through many of the chapters — is this idea that memory is unreliable and that it’s actually a creative process. We can’t harken back to CCTV footage in our brain because that doesn’t exist. What we have is our understanding of [what happened], our story of it. Our memories carry a lot of the DNA of how we understand ourselves — our insecurities, our fears, and also our hopes. And I think that that’s both beautiful and a bit treacherous.

“I’m not — and no one is — the perfect, reliable narrator. I am very reluctant to say I was the perfect victim and these were the perfect villains and bullies; I was good, they were bad. [For example,] I have a chapter where I hear from one of my childhood bullies on a gay dating app years later. I feel bitter at first. Like, what the hell, you were gay when you were making my life a living hell? But then I’m pausing to think, What does that have to say about the way violence works? So the book is about the stories we tell ourselves in order to understand who we are in the world. It helps us ask: Am I a good person? Am I a capable person? Am I a person who can actually give someone else advice?”

In the book, you also talk about coming to terms with internalized homophobia and racism. You write, “I knew I’d supposedly been stewing in these concepts” — toxic masculinity and homophobia — “my whole life and that my thoughts had been shaped by them.” Tell me a bit about what you’ve done with that realization.

“I grew up Catholic — I’m ex-Catholic now — and very core to the idea of being Catholic for me was the idea that you are a flawed person and that if you want to become better, you need to repent. I find that to be pretty symmetrical with the conversations around internalized homophobia or internalized racism. [There can be] this idea that these bad thoughts have worked their way into my brain, and my job is to punish myself every time that they manifest.

“But I think that the act of identifying and trying to work through [these internalized ideas] doesn’t have to be a painful one. It can be a really fruitful conversation you have with yourself. It can feel liberating, educational, rehabilitating. I still have things that I have to work through. And I can’t let myself be so afraid to have those conversations that I shut them out. It is really difficult. But I think that that’s just part of being a person who is aware of the way they move through the world.”

Has the pandemic changed the way you give advice at all?

“It has definitely rearranged my priorities and changed the way I see myself and talk to other people. I think confronting mortality and loneliness the way we have over the past year-plus has really made me lower the stakes in a healthy, productive way. So when I’m talking to someone that I haven’t seen in a long time, and maybe the conversation is a little awkward, there’s now a part of my brain that’s just like, ‘This is okay, this is not the end of the world.’

“So of course it’s changed the way that I give advice, just because I think that I have a renewed appreciation for the little things — for just the trappings of life — that we took for granted on a daily basis before. I got a lot of interesting questions about trying to date, trying to make peace with yourself, trying to make friends during the pandemic, which I found pretty difficult because everyone’s means of communication has completely changed… But I’ve also been really impressed with the way that I and other people have been able to adjust and do what we need to do and maintain ourselves throughout this whole thing. So I think that we’re all tougher than we think.”

Has there been an advice column question you’ve gotten lately that you’re really excited to answer?

“Yeah. I am writing one right now. It’s just a person who is a little discontented with the way his life has gone. He recently divorced his wife and he’s seeking a new life and trying to be the person he used to be before all this happened. He’s feeling: How can I be happy when bad things are sure to happen, and I can’t really control that? Am I just going to find someone else, marry them, we’re going to fall out of love, and it’ll end in another divorce? Am I going to find a better job and then get bored of it? And I think that’s really interesting, this idea of persevering through what you know is going to be a bumpy ride, which is sort of what life is all about. If a question stirs my emotions and I’m passionate about it, I will read it and I will immediately write a response, just freeform. Then I’ll take two weeks and come back to it. And then I’ll sort of Papi-ify it. I’ll edit it and I’ll put in little jokey jokes and turn it into a real recognizably ¡Hola Papi! column.”

Where do you go when you need advice?

“You know what, I am not that great at seeking out advice. When I’m dealing with something, I usually have this attitude of, ‘Well, we’ve just got to get through it,’ and I’ll just push through as best as I can. Usually if I’m real upset about something, I’ll call my mom and she’ll just tell me to go to sleep, which is always great advice. I don’t know if you’ve ever just showered and gone to sleep, but you wake up an entirely new person.”

Wow, my dad gives me the same advice. Parents! So my last question: In your own words, what’s the difference between wisdom and advice?

“I would say I have a lot of wisdom and not a lot of advice. My preferred job in life would be like an Oracle of Adelphi situation, where I can just speak in riddles and everyone deciphers them later. That’s what wisdom feels like. You have to sit with it and try to understand and interact and engage with it more than advice. But there’s no jobs for Oracles anymore. You have to run a column.”

This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Black Moms & Daughters Share Their Best Advice

Why All The Good Social Media Is Gay

Does My Eating Disorder Make Me A Bad Feminist?

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/3zaAn5s

via IFTTT