R29Unbothered continues its look at Black culture’s tangled history of Black identity, style, and contributions to the culture with ROOTS, our annual Black History Month series. In 2022, we’re redefining Black excellence while celebrating where our past, present, and future meet.

So it happened again.

I was lying in bed reading a book instead of forcing myself to watch Succession. I’m trying my best to get through the series to know what all the memes are about since I was late to the hype. I don’t comprehend imperialist white supremacist dialogue that well, so the literal white noise tends to put me to sleep until I’m violently startled awake by the hollers of Logan Roy cussing out his kids.

I decided to choose peace before bed, even if it meant I’d still be awake at 3 a.m. On this particular night, I was getting into the pages of 9 Plays by Black Women edited by Margaret B. Wilkerson. Wilkerson’s introduction was drenching me in new Black-ass information. I was familiar with the work of Beah Richards, Lorraine Hansberry and Ntozake Shange, who are a few of the Black playwrights featured in this anthology. But I didn’t have any real historical context for Black women playwrights in general — which is why I was reading the book.

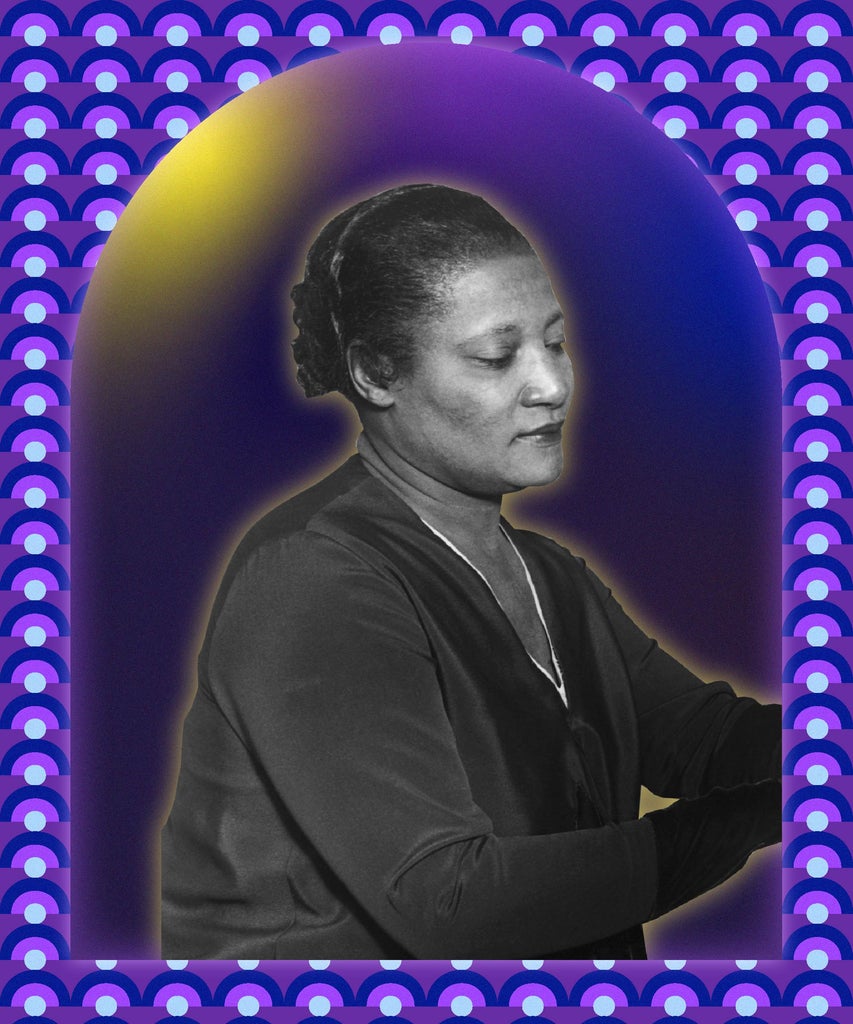

9 Plays unintentionally led me down the rabbit hole of one of my favorite pastimes: self-appointed private investigator of Black queer and lesbian relationships across time. Wilkerson writes that the first play to be produced by the NAACP’s Drama Committee of Washington, D.C. was a “race play” — Rachel, by Angelina Weld Grimke — that became the first drama of record to be written and performed by Black people in this century. As a storyteller and performer, I take a lot of joy in knowing there was a time when Black non-profits, specifically the NAACP, actively sought to fund and support emerging artists to create their work. These days you have to already be famous or featured on The Shade Room to get a dime from organizations to tell a Black story. While the NAACP was influential in funding Black artists during this time, it’s important to mention that their selection process was deeply rooted in colorism. Even with the power to make it possible for “the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relative to the lamentable condition of ten millions of Colored citizens in this free republic,” as stated in the original playbill for the production, they often granted this type of culture shifting influence to light-skinned Black people. This is true even for Grimke, who had a white parent and a bi-racial parent but was the first Black person of color to have a play performed for the public.

When the lovers, friendships, and families of Black Queer historical figures of our past are buried in the footnote of their contributions to Black history, the erasure directly impacts our views on what’s possible for our Black futures.

I should also mention that Wilkerson’s book of plays is pretty old. It’s so old that there’s an ad on the final page recruiting readers to volunteer against illiteracy with the Coalition for Literacy that reads: “By the year 2000, 2 out of 3 Americans could be illiterate. The only degree you need is a degree of caring.” So after reading the introduction, I immediately opened Google to find out more about Angelina Weld Grimké since I had never heard of her before.

Yes, she wrote the letter to the same Mary P. Burrill who was also a notable Black playwright during the Harlem Renaissance and is aggressively described as the “roommate” of Lucy D. Stowe. Yes, the same Lucy D. Stowe who was Howard University’s first Dean of Women and a founder of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first sorority established by African American women. When I’m deep in my process as a private investigator of Black queer and lesbian relationships across time, I’ve discovered that where there is one Black queer person, there are always many. We may be invisible to some but we are never alone.

I started with the Wikipedia page and there it was under “Sexuality.” I always know I’m about to get some good historical tea when there’s a section entitled “Sexuality” instead of “Personal Life.” Grimké was rumored to be bisexual or a lesbian. The only threads of this can be found in the interpretation of her unpublished work found after her death and because of a letter she wrote when she was 16 years old. According to Mark Perry’s Lift Up They Voice: The Sarah and Angelina Grmiké Family’s Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders, Angelina wrote a letter to Mary P. Burrill that read “I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope, darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife! How my brain whirls, how my pulse leaps with joy and madness when I think of these two words, ‘my wife.”

To Margaret B. Wilkerson’s credit, her introduction in 9 Plays by Black Women does mention that a significant contribution of Black women playwrights was their willingness to include lesbian and homosexual relationships as a substainal part of Black women’s reality and therefore, a part of the creative retelling of our stories, even on the stage. However, Wilkerson refers to that contribution as “new” at the time her book was published in 1986, when in reality, Black lesbians are among the originators of the art form.

This is what every Black History/Futures Month is like for me as a Black queer woman who is still in the process of searching for myself. I am constantly stumbling upon slightly cracked doors that lead to Black queer life in the legacy of some of the most legendary Black innovators of our country’s history. Digging for legible love letters penned by Lorraine Hansberry to her crushes and lovers. Yearning for photos of A’Lelia Walker twirling with a lover of her size, complexation, and desires at one of her fabulous Dark Tower Parties. Excavating for the comedy of Danitra Vance who was almost forgotten and rarely celebrated as the first Black woman to become an SNL repertory player in 1985. Queerness is not some new modern phenomenon that has fallen upon Black communitties. In fact, it is my deepest held belief that Blackness is inherently queer and at odds with the limited imagination of heteronormativity.

We’re already aware of the ways in which these Black trailblazing artists are hidden from the whitewashed retelling of American history. But when the lovers, friendships, and families of Black Queer historical figures of our past are buried in the footnote of their contributions to Black history, the erasure directly impacts our views on what’s possible for our Black futures. Simply adding notable Black Queer and Trans folks to our Black History Month celebrations is inadequate. We must be in a constant practice of addressing our internalized homophobia as a tactic to eliminate anti-Blackness in the re-memoring of Black history. We must also welcome the presence of queerness as an essential strategy to the advancement of all Black people. We cannot celebrate or even love what we don’t see. And I love Black people. Don’t you love Black people?

I cherish every time an ancestor reveals themselves to me. I’ve moved beyond simply exclaiming “I didn’t know they were gay!” to “I see you. I’m sorry they made you feel like you had to leave this part of yourself out of the narrative.” Before I had the courage to name myself as Black, queer, and figuring it out, I too wrote myself into being in my journals. I screenshot sweet text messages of me declaring my love and excitement for whoever I was loving on at the time. I snapped morning afterglow selfies with baes so that at the very least, even if the words never came out of my mouth, I wanted to make it easy for new generations to see who I actually was if they ever came looking for me. The least we can do when we find our Black Queer ancestors is to say so. We must do more than whisper their truth; we must honor them for it. Happy Black Futures Month.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

The Queer Black History Of Rioting

How Black Women Are Tearing Down Homophobia

Lil Nas X’s ‘Montero’: A Coming Out Story

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/4BYE8LZO6

via IFTTT