We’re living in a world with no off switches and our burnout is at a boiling point. Powered Down explores how the system has failed us and what we can do to find our way off the hamster wheel — for good.

Life in Alaska wasn’t for Katelynn Sortino. The weather was one thing, but she was also burned out from her job as an addiction counselor there, which she’d been doing for the last 12 years. Plus, the dating scene was bleaker than the tundra itself.

The pandemic only made things feel more untenable. After a listless few months working through lockdown, she downloaded a dating app on a whim. Sortino soon hit it off with a charming, family-oriented person, and found they had a lot in common. The only issue? He lived in Morocco. But their conversations via text and FaceTime were so deep that by January 2021, after getting vaccinated, she was buckling herself in on a plane bound for North Africa. She stayed for three blissful weeks, and he proposed. She said yes, then went home and quit her job. She sold her car, packed up her stuff, and moved to Kénitra to be with him.

Changing her life was easier than she’d initially thought it would be. She had savings, and the logistics were manageable enough. She’d been itching to get out of her job and town anyway, so the goodbyes weren’t so difficult. But while she and her partner were happy, she soon realized that even the most seismic shift in scenery and routine weren’t enough to cure her lingering burnout and anxiety. As Sortino puts it, “No matter where you go, you bring your problems with you.”

Many people made these kinds of big life changes in the pandemic. We moved. We quit as part of the Great Resignation. We broke up, came out, got married, ended friendships, and had babies. There were many good or practical reasons why we chose to do something different — we wanted warmer weather, a lower cost of living, a more creative job, to find true love. But no matter the specifics, a major throughline had to do with happiness. We thought the new gig, partner, or environment would give us more purpose, improve our moods, or generally impact our wellbeing positively. We wanted, well, a better life.

But we didn’t necessarily get it.

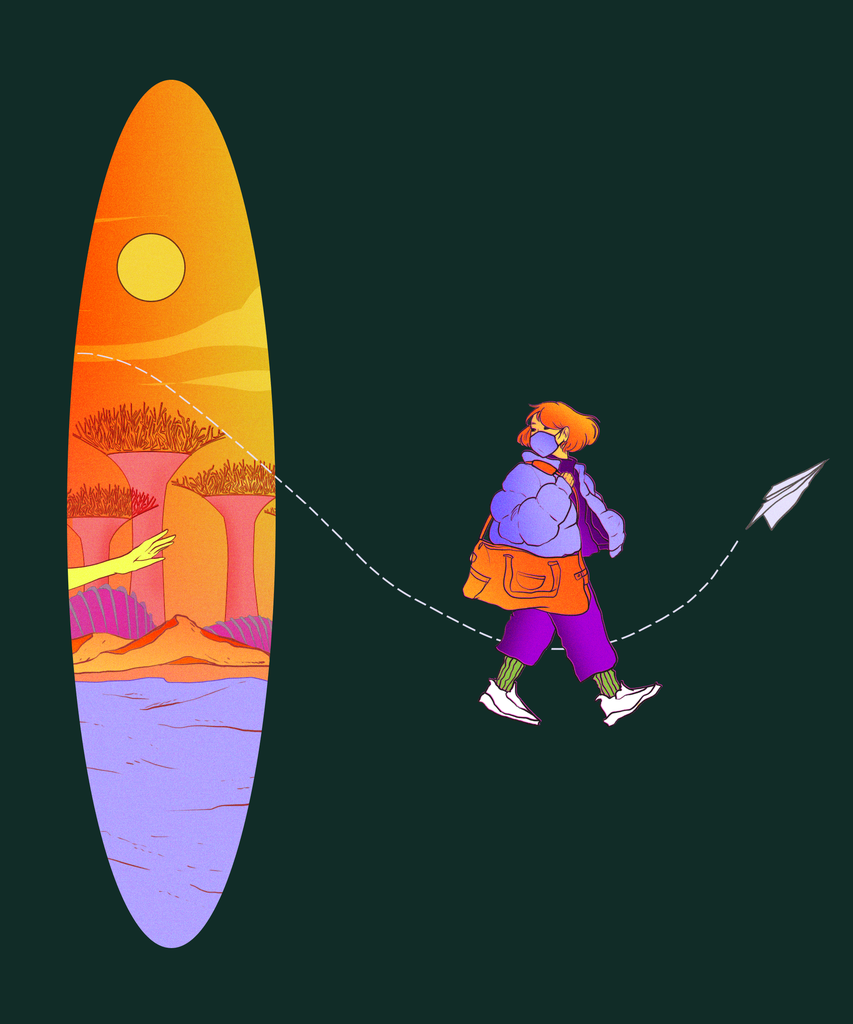

Even after making these big changes, like Sortino, we still weren’t happy. “It calls to mind the visual of the cartoon where the person is walking around and the little rain cloud keeps following them,” says Steven Meyers, PhD, a clinical psychologist and professor at Roosevelt University in Chicago.

But the thing is, we really didn’t expect that raincloud to follow us, and, when it did, it was pretty disconcerting. For many, it’s a human instinct to try to fix things if they feel broken. And, to chase the sun. Especially when things are out of our control — as they have been during the pandemic — we want to make them feel better, in any way we can.

But sometimes, these radical changes were covering something else up — they were a way to unconsciously avoid dealing with an underlying struggle with mental health or extreme stress, perhaps brought on by the Groundhog Day feeling we’ve all experienced in the pandemic. Or, they were a false solution to an internal problem we hadn’t yet acknowledged. “When people are struggling with depression or major stress, they may not be as accurate as they’d like to be about identifying the source of their unhappiness,” Dr. Meyers says. “They think if they remedy what they perceive as the primary source of misery in their life, that change will make them feel better.” But that’s not always so.

We thought the new gig, partner, or environment would give us more purpose, improve our moods, or generally impact our wellbeing positively. We wanted, well, a better life. But we didn’t necessarily get it.

Sortino was running toward love, sure, but she was also running away from a pretty intense situation that was only made harder over the past two years. “I was so unhappy and trying to switch up my life before the pandemic even started,” she says. “I had been working two jobs, sometimes up to eighty hours a week, to pay off my loans and save up enough to travel for a year. I planned to leave everything in June 2020, but then the pandemic hit and there was nowhere to go, so I stayed. But my anxiety was getting worse all the time and the pressure of working so much was breaking me down.” Her mental health deteriorated and the burnout festered as she worked in healthcare during the worst of the pandemic.

And all this wasn’t so easy to shake when she moved to Morocco. “You don’t realize how much you’re on the hamster wheel until you climb off,” she says. “Even though I wasn’t in my job anymore and was doing more freelance work, I felt I could always be doing more and I was bringing all this stressful energy with me, no matter where I was or what I was doing.”

Sortino was feeling this, in part, because she was dealing with an internal struggle that an external change couldn’t fix. Other times, though, we can still feel unhappy after a change, not because it wasn’t the right move, but because even positive change can be stressful, Dr. Meyers says. There’s usually an adjustment period (and, more often than not, a boatload of paperwork), and that’s why we don’t feel immediately better even after pulling up our roots and moving to Montana or Miami or Morocco or starting a new job or going back to school. Change is often uncomfortable, and “we’re hardwired to veer towards things that are more comfortable,” according to Alfiee Breland-Noble, PhD, MHSc, a psychologist, mental health correspondent, and founder of the nonprofit, The AAKOMA Project.

But in some circumstances, well, we end up believing we made the wrong change altogether, or that we need to make an additional change to be happy. Eloise Skinner, for example, decided early on in the pandemic that she wanted to leave her job as a lawyer. She was unsatisfied working from home and missing the camaraderie of being in an office.

She also hoped to find a “more peaceful” alternative to corporate life in London, England. It wasn’t until she quit and chose to write a book about finding purpose that she realized how much she missed about her 9 to 5 — having coworkers (even if they were on Zoom) and a time to clock in and out. So, after a few months of writing in coffee shops, she decided to make another change and start her own business. It was built off the same concept of her book, so it let her be creative, but also gave her the structure and company she craved. “For so long, I was working up to leaving my first job, and after that, I felt a little like, ‘What happens next?’ I felt a bit restless and empty,” she says. Making the second change alleviated much of this feeling. Her experiences “taught me the importance of continuing to re-evaluate and re-assess my life,” she reflects.

As 30-year-old Skinner realized, sometimes one change isn’t enough. In other words, there might be a “constellation of factors” that cause discontent, as Dr. Meyers puts it. Maybe one shakeup helps, but it doesn’t produce a large-enough effect — the edge is taken off, but you’re still unhappy. We tend to stack decisions on top of each other like Legos, and there’s a reason they all seem to fit together. But if you don’t like the direction your life has gone, getting to where you want to be may involve taking apart the whole stack, rather than just the piece on top. For example, if we think we can shift our circumstances by cutting out one friend we perceive as a bad influence, it may not be enough, because we’re still in the same environment and around other like-minded people and triggers.

To be clear, we’re not suggesting you should join the tail-end of the Great Resignation, move to a place where the rent isn’t skyrocketing, and break up with your partner all in one fell swoop. In fact, if you’re making multiple changes, it can be helpful to make them incrementally, so you can “control” for what factors are impacting your happiness, like a scientific study would. “I’m not saying it’s impossible to make multiple changes all at once, but… I think it’s easier for our individual, emotional wellbeing if we try not to tackle too much at once,” Dr. Breland-Noble says.

But whether you’re making one or seven big life changes, there may come a time you feel you’ve made the “wrong” one. The good news is, if this happens and you end up still feeling dissatisfied, most changes can be undone. And, in the rare case, they can’t be, Dr. Meyers recommends reminding yourself that you made the best decision you could at the time with the information you had. “A lot of people… play the ‘woulda, shoulda, coulda’ game,” he says. But this isn’t helpful. “If you can’t go back, you can make choices to propel you forward,” he adds. “New jobs can be left, and new relationships can end. There are not very many decisions in life that are truly permanent.”

And if you’re not sure if you’ve made a huge mistake, just have the jitters, or there’s something bigger going on you need to address internally, try continually checking in with yourself about how you’re feeling, Dr. Breland-Noble suggests. “People will plan for the logistics of a change — where’s the money going to come from, how will we get there — but emotionally we don’t think we need to prepare as much,” she says. Ask yourself: “How are you feeling, pre-change, mid-change, and post-change?” she adds.

Look at your mood, your habits, and how they impact each other, she suggests. This kind of emotional tracking can help you determine if your unhappiness is situational or broader, and also help you pinpoint activities that make you feel better (or worse). And, of course, there are apps that remind you to check in daily. I personally have used Breeze, which reminds you to track what emotions you’re feeling — joy, anxiety, excitement — along with what activities you’ve been up to. Alternatively, you can just set a calendar reminder to check in, or journal about it at the end of the day. By being mindful, Beland-Noble says, we can reset, find equilibrium, and become more in tune with ourselves and, thus, we can better determine what changes might feed our souls.

So far we’ve only been talking about changes we choose for ourselves. When the change is forced, well, “it throws you for a loop” in a different way, Dr. Breland-Noble says.

That’s what happened to Dominique Bouchard. In February 2020, the 30-year-old gave birth to her daughter and experienced severe postpartum depression and anxiety that made it difficult for her to get out of bed. That May, in the height of the pandemic, the family moved from downtown Toronto, ON, Canada, to the suburbs. They had more space for their growing family, but she felt isolated. “We were now living on a street with only one other Black family,” she says. Not to mention, Bouchard didn’t exactly have time to cultivate a new community. She was hard at work at a new business she was building, a creative service agency. “I was burning the candle at both ends, trying to be a good caregiver for my child, and aiding everyone but myself,” she says. To make things even more challenging, in September of that year, her husband was diagnosed with stage two non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

When change is forced on you, as in Bouchard’s case, it can be more difficult to process. This is because it feels so out of your control, especially so in a global pandemic. You have to give yourself space to take care of yourself, Dr. Breland-Noble says. In some cases, you even have to forgive yourself. “What some people do is beat themselves up,” she adds. “They say, Why didn’t I see this coming? Or, I should have quit before they fired me. That’s not helpful. It puts us in a different headspace and doesn’t allow us to move forward and heal… If a change is thrust upon you, the two best things you can do are to give yourself some grace — be kind to yourself — and to allow yourself to grieve before you do anything else.”

Bouchard found this to be true, but it wasn’t easy. “I’ve had to learn to prioritize myself,” she says “And it feels terrible to do that sometimes.” It was a struggle to learn to accept help from her in-laws with childcare, for example. “It was also difficult to hire another person for my team,” she says. “Especially as a Black woman, where we’re brought up to believe you have to work twice as hard to get half as far, it almost feels like cheating by asking for help and by asking for space. Learning to do that has been a huge hurdle I’m still working through, but it’s a muscle I’m learning to flex.” But she got some good training on this by seeking help from a therapist — actually, three of them. It took her a few tries to find the right fit.

In seeking guidance through therapy, Bouchard says she was better able to understand her “greater purpose and give myself the permission to take daily steps in walking in that purpose.” As Dr. Breland-Noble puts it, when you’re struggling with change — yes, both chosen and forced change — there is one, main common thread: “You’re still going to need support.”

Help can come in all forms: therapist, psychiatrist, a support group, or a friend or family member you trust (who has no stake in the game, ideally). “Sometimes our feelings or options become clearer only when we explain them to someone else,” Dr. Meyers says. There is power in talking things out, especially if you can take into consideration any biases the folks you’re talking to may have.

And importantly, “support reminds you that you are not alone in your struggle,” Dr. Breland-Noble adds. “It teaches you that you are worthy of love and care, and that other people will show up for you when you need them.”

Like Bouchard, when Sortino realized she was bringing her burnout with her to Morocco, the 32-year-old relied on her systems of support. She turned to her husband, her mom, friends, and her pet bichon Isla. She’s also looked into online therapy and read many self-help books. Today, she’s still actively adjusting to the change she made and the challenges that have come with her new environment, like not knowing the language. She and her husband have thought about moving to another country, such as Germany, so they can start over yet again — this time together.

But for now, Sortino is focusing her energies on trying to “be happy internally no matter where I am.” She’s learned that external changes can feel exciting and proactive, but they can’t necessarily solve everything. “I assumed moving would fix internal problems, but I still had a lot to work through,” she says, adding she’s been actively working to find peace and joy in her day to day.

“I’m not waiting to allow myself to be happy until we buy the comfy couch we’ll have for the next 40 years, or until we move to the next place,” she says. “I don’t want to live my life thinking, Well someday I’ll be happy but can’t be until I get to the perfect place. I’m learning that you don’t need to have total stability in order to feel centered.”

If you are experiencing postpartum depression, please call the Postpartum Support Helpline.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or the Suicide Crisis Line at 1-800-784-2433.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

Latinas Lead the Great Resignation—Here's Why

What Does The Great Resignation Mean For Workwear?

I Moved To A New City Alone. Then The Pandemic Hit

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/Ne48Tv9

via IFTTT