Before her death, master printmaker Belkis Ayón employed collagraphy to challenge the dominant narratives of Cuban culture that whitewashes and sanitizes its history. Though she was not necessarily political or religious, Ayón’s life-size and often panoramic installations helped to preserve the legacy and oral tradition of Abakuá, the all-male secret society with roots in present-day Nigeria. Her signature black-and-white figures, which at once appear human and otherworldly, put a magnifying glass to the ancient West African fraternity that made a home in 19th century Havana.

Like Ayón, Black women and men around the world have used art as protest and reclamation for eons. Historically and to date, it has been a means for people of African descent to express our experiences and perspectives, assert our humanity and dignity, and do away with the dominant narratives and power structures that have marginalized and oppressed us. More critically, Black art has long played an indispensable role in preserving and transmitting Black identity, culture, and history, as well as inspiring and empowering future generations of Black artists and activists.

Look no further than our own Harlem Renaissance and its definitive text in Alain Locke’s The New Negro. In spite of its shortcomings and emphasis on assimilation into white bourgeoisie, the achievement of The New Negro was palpable and, along with the Renassaince, succeeded in laying the groundwork for all depictions of fiction, poetry, and film of the contemporary Black American experience. Among the many, sometimes polarizing declarations made by Locke in the seminal volume, which included contributions by Afro-Puerto Rican historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg among other Black immigrant writers, was a “spiritual coming-of-age” by way of our collective intelligentsia. His enthusiasm was prodigious and perhaps prophetic.

“Black artists and art remain at the fore of resistance movements near and far, from Caracas, Venezuela, to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Oaxaca, Mexico, while also providing a space for Black people to participate in love and joy.”

marjua estevez

Just as in 1925, Black artists and art remain at the fore of resistance movements near and far, from Caracas, Venezuela, to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Oaxaca, Mexico, while also providing a space for Black people to participate in love and joy. Iterations of such resistance and a profound refusal to die is found in Haitian tire machèt, Colombian champeta, and Afro-Mexican zapateado, among other countless forms of song-and-dance and self-expression. For instance, capoeira, a martial art that originated in Brazil among enslaved Africans, is proof our creative ingenuity and autonomous expression can transcend us even when we’ve been stripped of our license to speak and deprived of our identities and cultures.

This Black History Month boasts a national theme of “Black Resistance” and is dedicated to exploring how Black Americans have addressed historic struggle and ongoing oppression. Following discussions of Afro-Latine invisibility and artistic statements around Bad Bunny’s historic performance at the 65th Grammy Awards, it is apropos to extend this theme beyond the shores of the United States, a nation built on the backs of its immigrant populations. We hand the proverbial mic to Black poets, dancers, photographers, entrepreneurs, and filmmakers around the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and Latin America using art not to prove we were here or why we matter but rather to insist our future depends on exhuming the past.

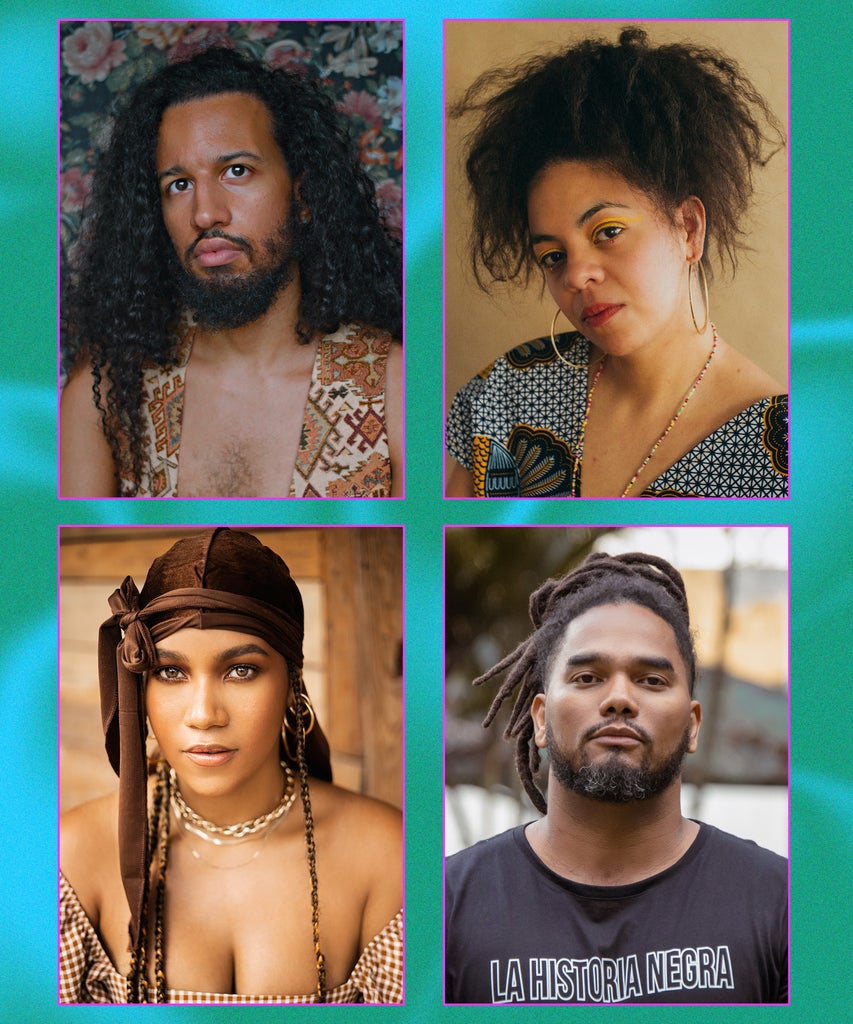

Melania Luisa Marte, Poet & Writer, Dominican Republic

Art for Black folks is very spiritual because our art has served as proof of our existence. It’s rooted in our survival and in celebrating our existence. As a poet, my chosen medium in the art form is a root. A root is meant to ground — to ground your expectations, your ill wishes, and your dead ends until they come up on the other side as something that is healing, joyous, and beautiful, something that you can use to keep transcending.

To me, poetry is a beautiful and necessary way to shift culture and reclaim what belongs to Black people. In my collection of poetry, Plantains and Our Becoming, I refuse to go back to the “unknowing,” or back to when we allowed people to whitewash our culture and take us out of our element. When Black artists and creators produce with this intention, we refuse to go backwards, we refuse to be unheard. We know now more than ever that to be without culture is to be without spirit. I know we want to live in this world where everyone should be allowed to participate and embrace all things, but we also have to understand that there are things that are sacred to Black people and cultures. There are systems of worship and spirituality that were once stripped of afro-descendants that are today being bought and sold to us by the very same communities that demonized them.

When Black artists exercise our genius, it allows us the willpower to emancipate ourselves spiritually and to really explore the full breadth of our ancestry, in a world that has time and again tried to eliminate us no less. This makes Black art, or art by people of African descent, inherently political.

Ebony Bailey, Documentary Filmmaker, Mexico

Growing up Blaxican in a Central California community made up of mostly non-Black Mexican Americans, I wanted my work to focus a great deal on how Black life impacts other people, especially other Black people. At the intersection of Blackness and Mexicanidad, my mother being Mexican and my father African American, film and photography have helped me connect with a lot of people around the African diaspora in Latin America. It’s helped me to learn to interpret different stories about Blackness and express them in a beautiful way — like when I learned about Brazilian capoeira, a mix of dance and martial arts, or Haitian tire machèt, which combines martial arts with fencing. These are artistic practices and tools of liberation for Black people.

You can find art forms rooted in Black resistance across the Americas, including in Mexico. For instance, during the colonial period, the Spanish prohibited people from using drums, so Black and Indigenous people developed zapateado, which is a way of making beats with your feet and body. When I first learned this history, I was in awe. But then it forced me to consider the gravity and longevity of Black erasure in Mexico, and how one of Mexico’s most fundamental dances started in Black society.

This is what inspired me to use film as a way to preserve oral history. In my recent project Jamaica y Tamarindo, I intentionally didn’t interview so-called experts because I wanted afromexicanos to be their own experts on camera. In many ways, this impulse to create in this way is inherited. In such a colonial world, where our bodies and voices are constantly being controlled, policed, and violated, I believe that autonomous self-expression is a way of liberating ourselves from everything western, from this constant surveillance of our humanity. I believe it is an inherent form of resistance when we self-express without the influence of whiteness.

Elías Ramón, Family Genealogist & Bomba Practitioner, San Juan, Puerto Rico

I’m a family genealogist and anti-gentrification community activist. Of Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Haitian descent, I am also a part of the Orisha tradition in Lucumi. Much of what I do is tied to ancestral spirituality. I am currently focused on training professionally in the school of traditional bomba, a passion I pursued when I moved to the archipelago during the pandemic.

A lot of what I do affirms connections among Puerto Ricans, which disrupts the paralyzing individualism that the west indoctrinates us with. When Black American tourists come to Puerto Rico, and I see them in the bomba circles, I prioritize them. As a genealogist and a historian, I know that the Caribbean was the gateway to the Americas before Africans were taken to what became the United States. The way I look at it, we don’t know who was in the Caribbean before they were separated from relatives and taken to North America. In that sense, we don’t know who is coming back home. Understanding this, I often ask Black-American tourists, “why aren’t you shaking your ass by the drums? This belongs to you, too.”

While in the Caribbean, we had the privilege of being able to reconstruct the drum, for a long time, our Black-American siblings did not. But, as we know, African imagination doesn’t stop; we improvise. So what do Black Americans do? Create tap dancing, stepping, beatboxing — they use their body as the drum, which is also an act of resistance, whether or not one recognizes that. Negro spirituals, the tonality, vibrations and vocals used, these things are connected to frequencies you find in vodou music or palo. That’s why gospel songs have that spiritual essence; it’s touching on this frequency, because that’s ancestral. We may not always know how to sing in Yoruba, but we have the tonality. Similarly, elements of milly-rocking, two-stepping, lindy-hopping, and even breakdancing can be traced back to bomba music. For eons, our people have survived, and have created optimal lives of joy and happiness, through song and dance.

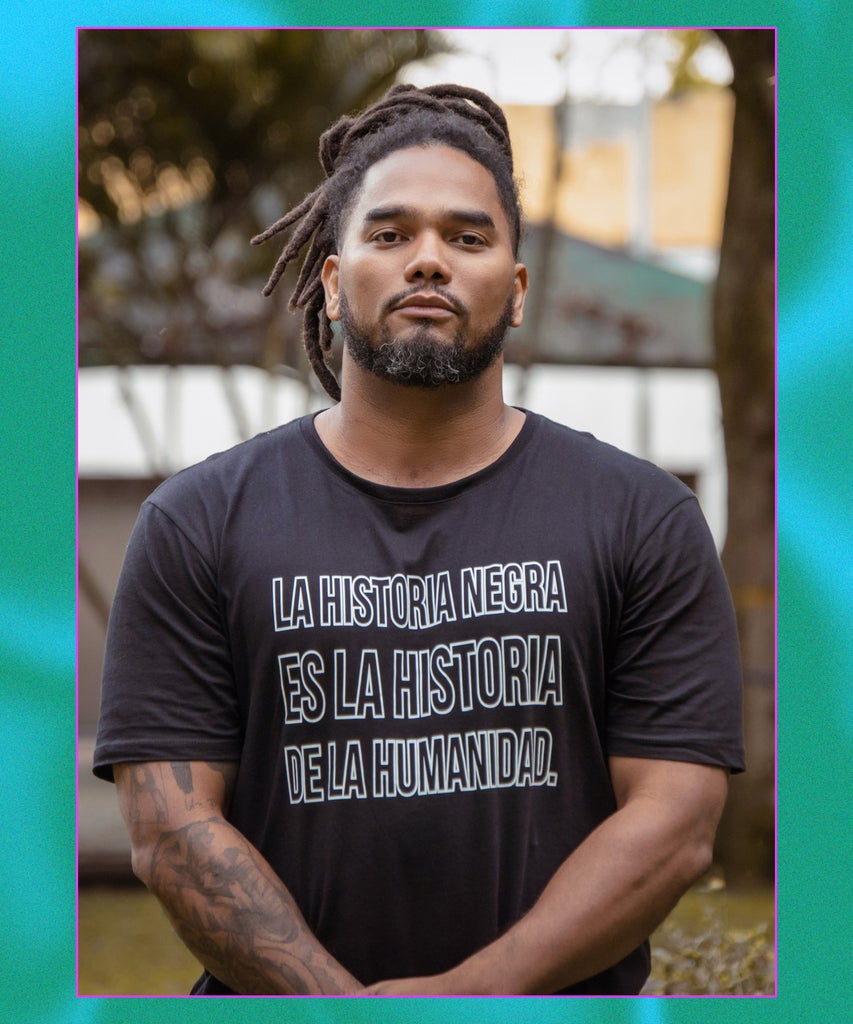

Shamyr Caicedo, Educator & Entrepreneur, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

Art is one of the most necessary tools that Black communities all over the world have long used to express our sentiments, share our stories, and prove that we were here. Fashion, in particular, has proven to be an incredibly useful tool in contemporary times and discourse. I like to say that fashion has turned into a mobile art where every person is dressed in their views or conditions, the politics of what it means to be human.

Our brand, Basico Pero Nitido, has helped us create political discourse around who we are as a people and offer a renewed sense of pride and love. It has allowed us to create and spread a pedagogy that the communities we serve have access to and they transport to new communities. It’s the kind of content that we’ve always wanted to create and share.

Our brand is especially necessary in a country like Colombia, where we have historically erased the contributions and presence of Black people. I was born in a coastal town, Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. My work helps us understand the social dynamics of Colombia’s Black populations. We know our stories have been minimized, erased, and whitewashed, and that this has contributed to fracturing the pride, love, and dignity of communities around the African diaspora. This is why I have chosen art and fashion as vehicles to safekeep all the work that we have done here, so that our truths might endure and transcend. Our message promotes freedom. We want our communities, Black people here and there, to understand ourselves, our history and present, and to understand what we represent and reflect around the world.

Alejandro Pérez, Photographer, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Black and queer people already have to constantly explain ourselves and our humanity. Photography is my way of doing this without having to be argumentative about my own experience. I use photography to tell the stories that I believe are important to share. Photography allows audiences who would never listen to me to engage with my work. There’s a sense of freedom in that, in not answering to the white gaze. This is one of the more powerful elements of Black art.

In the Dominican Republic, we’re seeing more Black artists taking authorship of our experiences. More and more, we’re beginning to talk about issues surrounding race, gender, and sexuality through a very Black experience. Even personally, I started to regularly practice and seriously pursue my photography here after living in Spain for 17 years. Self-expression is very intuitive for disenfranchised people. It’s very intuitive of us to bring everything that we are into whatever spaces or positions we occupy, be it through words, images, or clothing.

For this reason, it’s important to also create spaces for the kind of discourse our art might produce. This is what I aim to do with a new podcast I created with my good friend Zahira “Bad Dominicana” Cabrera, another Black Dominican artist living on the island, called Tú Supite. It centers Black voices, queerness, and resistance with a critical eye toward what’s happening on the grounds in DR, while still having fun and being among family.

Alfonsina Lugo, Creative Director & Singer-songwriter, Caracas, Venezuela

Black music all over Latin America, from Colombia to Panama to Brazil, has always been instrumental in spaces of emancipation. Oftentimes, our biggest celebrations are commemorated with the drum. This is a very African tradition, one that was once stripped from us. Yet, today we see non-Black musicians around Latin America take up the discipline. This isn’t unusual. There’s a huge Black Caribbean culture in Venezuela that influences the entire country, but as a singer, I have had little access to Black Venezuelan music. What’s going on here? I know we have this Afro-music in our fabric, but why do we know so little about it?

My podcast Ancestras is a response to this. It’s an investigative music podcast where my team and I tell stories about these genres and share this vital information to people of my generation. My work is about excavating our ancestral rhythms and dances so that we can pass this information on. Not long ago, I learned that my grandmother was the child of people who were enslaved. As someone who comes from a family that champions the arts and music, my work is dedicated to those who came before me. I think art gives communities of African descent a blank canvas for our greatest truths, and that alone is a form of spiritual liberation.

Yaissa Jiménez, Poet & Writer, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

I come from a place called Los Mina in Santo Domingo, and it’s a barrio founded by cimarrones, Africans who escaped slavery. The legacy of that village informs much of my work and how I move in the world. I’m a poet, but growing up, Black Dominican literature was all but banned. The only works I had access to was by white authors, the same people who would not consider me a poet. I had to go underground to find work that I felt represented in.

Today, my poetry has been a tool for healing, self-actualization, and knowledge. It is something that transcends me in a practice of love for my people. Poetry is a form of communication, and my art is the one thing that the colonial eye, that whiteness, cannot touch.

If I’ve learned anything from Indigenous land and Indigenous communities, it’s the fact that art, creation, and ritual are daily practices and necessary parts of everyday life. So, I am more concerned with Black art talking about our desires, our complexities, our humanity, and all the questions we want to raise. What happens when something trickles outside of language or away from the page, when something we’ve always known is no longer enough to express what we want to say, when we want to express our absolute joy, or an idea of joy that has nothing to do with whiteness? That is what I believe Black art does best and what it should always attempt to be doing. Black women in particular, by just existing in our skin, we can feel just a tiny bit of what we are capable of manifesting.

My art is obviously political. I think most art is because real lives are involved. But I don’t asterisk my work in that way because a big part of why I do what I do is to expand our people, offer us a sense of joy and celebration and reflection, that isn’t necessarily steeped in trauma or struggle.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/lZM4opn

via IFTTT