In a short Brazilian film starring an all-Black cast, a young girl frees her imagination on what she can become when she grows up. Dressing up like her role models, she plays with becoming a singer like Iza, an athlete like Daiane dos Santos, and a writer like Conceição Evaristo — all successful Brazilian Black women. At some point, her mother asks, “But you know you could be a Supreme Court Minister, too, right?” The daughter becomes confused. “Like who, mom,” she asks. The young girl has never seen a Black woman like her occupying such a powerful position. And a growing movement in Brazil aims to change that.

The fictional film, titled #MinistraNegra, is part of a campaign called Preta Ministra that addresses an existing issue in racially unequal Brazil: the lack of Black women on the Supreme Federal Court (STF). As President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva gets ready to nominate a new Supreme Court Minister, which is expected to happen in the following days or weeks, a growing, countrywide movement is pressuring the government to choose, for the first time in Brazil’s history, a Black woman to integrate the institution.

“It’s a symptom of racism and misogyny.”

Tainah Pereira

Black and Indigenous women have been absent from the STF since its inception. In 132 years, 171 ministers have gone through the institution. Of them, three were Black men, and three were white women. The homogeneity that has configured the high court’s body of ministers through history is far from a random fact.

“It’s a symptom of racism and misogyny, which have structured the institutionality in Brazil,” Tainah Pereira, political coordinator of Mulheres Negras Decidem, one of the groups campaigning for a Black woman minister, tells Refinery29 Somos. Currently, Lula’s allies have predominantly suggested jurists (judges and lawyers) who are affluent, white men from Southeastern Brazil. “The alienation of the majority [women and Black people] from the highest domes of power is material and symbolic,” she adds.

According to Maysa Carvalhal, a lawyer with the Institute of Defense of the Black Population, another organization that’s involved in the campaign, a Black woman minister would bring a missing perspective to the STF that would be essential to advancing just and humane agendas that have been deemed “controversial,” such as the legalization of abortion and the decriminalization of drug use.

“It is more likely that a woman will be more empathetic toward decisions involving gender issues, that a Black person will be more sensitive toward a debate on incarceration, or a working-class person will have a more humanistic approach to voting involving labor rights,” Carvalhal tells Somos.

While the first vindication for a Black woman minister started in July 2022 (with the Black Jurists Institute urging for this nomination in an open letter), most campaigns gained momentum after June 2023, when President Lula nominated Cristiano Zanin, a white man, to replace Minister Ricardo Lewandowski, another white man, on the STF when the latter retired in April.

Since then, a growing number of activists, artists, lawyers, and politicians have been joining efforts to pressure Lula to pick a Black woman jurist after October 2, when another STF minister, Rosa Weber, will retire.

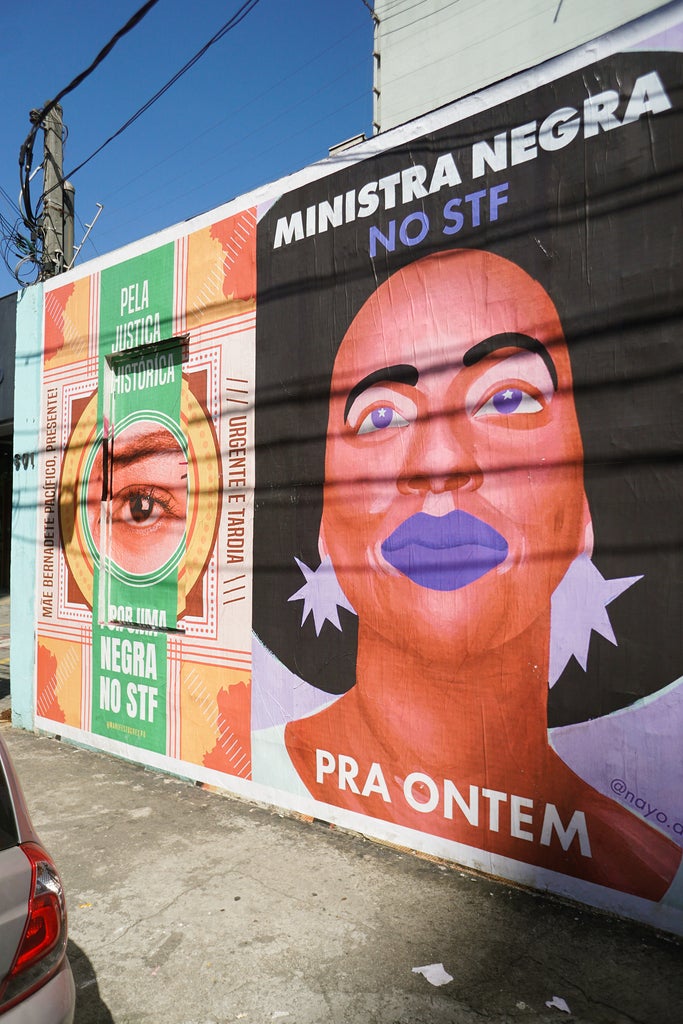

The campaign has been using media and public art to uplift its message. #PretaMinistra, created by the Defense of the Black Population and the Black Coalition for Rights, has recently been a trending topic on Brazil’s Twitter, or X as the platform has been renamed. On social media, Brazilians are sharing the aforementioned fictional short film, including a short clip where the young girl says, “When I grow up, I want to be a Supreme Court Minister.” On September 11 and 12, the film was also displayed at New York City’s Times Square.

“We know that this struggle is not restricted to Latin America. And we know how influential the United States is in political and economic decisions across the globe.”

Maysa Carvalhal

“We know that this struggle is not restricted to Latin America. And we know how influential the United States is in political and economic decisions across the globe,” Carvalhal says, recalling the power of multimedia for national and international Black-led movements.

On the streets, the project Juízas Negras para Ontem is bridging art and politics. Currently, 14 Brazilian cities — including Manaus (in the Amazon), Porto Alegre (in Southern Brazil), and Salvador (the Blackest capital of the country) — showcase the works of 24 Black artists. All of their artworks stir attention to the importance of the cause. In one mural, artist Ayala Prazeres blends her self-portrait with a powerful quote by Angela Davis: “When the Black woman moves, the whole structure of society moves with her.” In another piece, artist Dacordobarro juxtaposes images of her neighborhood (recognized as a quilombo urbano, an urban community that preserves its African heritage) with three Black woman jurists, and asks: “Can we imagine a Black minister in our country?” Similarly, Alisson Damasceno, an artist from Belo Horizonte, illustrated a Supreme Court Chair surrounded by Saint George’s swords, a sacred symbol for Afro-Brazilian religions.

“Where does the idea that Black women can’t occupy certain offices come from? This is the unrest that all the 24 artists had in common,” Nina Vieira, visual artist and curator of the campaign, tells Somos, adding that one of the artworks was handed to STF Minister Alexandre de Moraes.

Another initiative, “Tome Um Cafezinho Com Elas,” invites Lula to “take a coffee” and meet three Black female jurists who are capable and ready for the position.

Chosen by the Mulheres Negras Decidem movement, they include Rio de Janeiro’s Adriana Cruz, Bahia’s Lívia Sant’Anna, and Porto Alegre’s Soraia Mendes. At the time of writing, more than 102,000 people have sent letters to Lula’s office inviting him to have a coffee with these jurists.

“Where does the idea that Black women can’t occupy certain offices come from?”

Nina Vieira

While Weber retires on Monday, October 2, Lula recently stated that he has “no rush” to announce the next minister: “Everything has its time. I have to talk to a lot of people. I have to listen to a lot of people,” he said during a press conference this week.

When it comes to choosing the next STF minister, there is a lot at stake for the president.

“It is the most political nomination in the judiciary. More than a jurist’s professional competence, the criteria is, above all, political. It has to do with reliability and the proximity one has with the president,” Carvalhal says.

According to Estela Gonçalves, a lawyer who specializes in public law, trust is a fundamental criterion for choosing the next minister, too, because of the recent socio-political context of Brazil — including Lula’s political imprisonment in 2018 and the frustrated coup de état organized by supporters of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro in January 2023.

“He will choose someone he can trust with eyes closed. And, so far, he hasn’t expressed this degree of reliability toward any Black female jurist. This is quite serious,” Gonçalves analyzes, recalling that, on September 25, Lula affirmed that race and gender “won’t be criteria for his choice.” On September 27, movements organized a demonstration in Brasília to reinforce the agenda.

“Because of the campaign, some local Black jurists are, today, known by people from all over the country. This might open doors to other powerful spaces.”

Estela Gonçalves

In spite of what can play against the nomination of a Black woman on the Brazilian STF, Taynah Pereira feels optimistic as the campaign has already proven to be impactful.

“Ever since we started a more incisive approach in the campaigns, President Lula nominated Marcelise Azevedo to the Presidency Ethics Commission and Edilene Lobo to the Superior Electoral Court. He also raised the quota of affirmative actions in public administration offices from 20% to 30%,” Pereira tells Somos.

Gonçalves agrees that, regardless of Lula’s nomination, change is already taking place in Brazilian politics.

“Because of the campaign, some local Black jurists are, today, known by people from all over the country. This might open doors to other powerful spaces that are also relevant, if not in the Supreme Court, maybe a vacancy in the Union Attorney General. We are hopeful,” she says.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/7JKNj4C

via IFTTT