Few record drops raise the hair on my neck like the high-pitched staccato boom intro of “Pa’ Que Retozen,” the landmark lead from Tego Calderón’s 2002 debut album El Abayarde. “Digan lo que digan, vamo’ a gozarno’ la vida; tampoco a lo loco, protégeteme la mina, mija,” he rapped in catchy couplets about safe sex over a sweat-imbued, bachata-tinged sandungueo by DJ Joe. Twenty years later, the 19-track Caribbean mash-up remains an indispensable part of music history, introducing one of Puerto Rico’s most prolific lyrical exports and launching reggaeton around the world.

Before Daddy Yankee became the poster child for radio reggaeton and Don Omar the king of reggaeton romantico, it was el Negro Calde’s socially conscious and hip-hop storytelling that carried the bubbling genre into the mainstream and across international borders. A proud representer of Loíza, where the pulse of Black Puerto Rico resonates, Calderón understood viscerally that reggaeton heads were far from one-dimensional. And as a student of craft, Tego felt no need to compromise language for his need to celebrate the oft-vilified perreo culture that grew alongside the ascension of the genre. His breakout hit “Cosa Buena” became one of the first reggaeton videos ever to earn heavy rotation on Telemundo and served as a precursor to El Abayarde, his studio debut under White Lion Records.

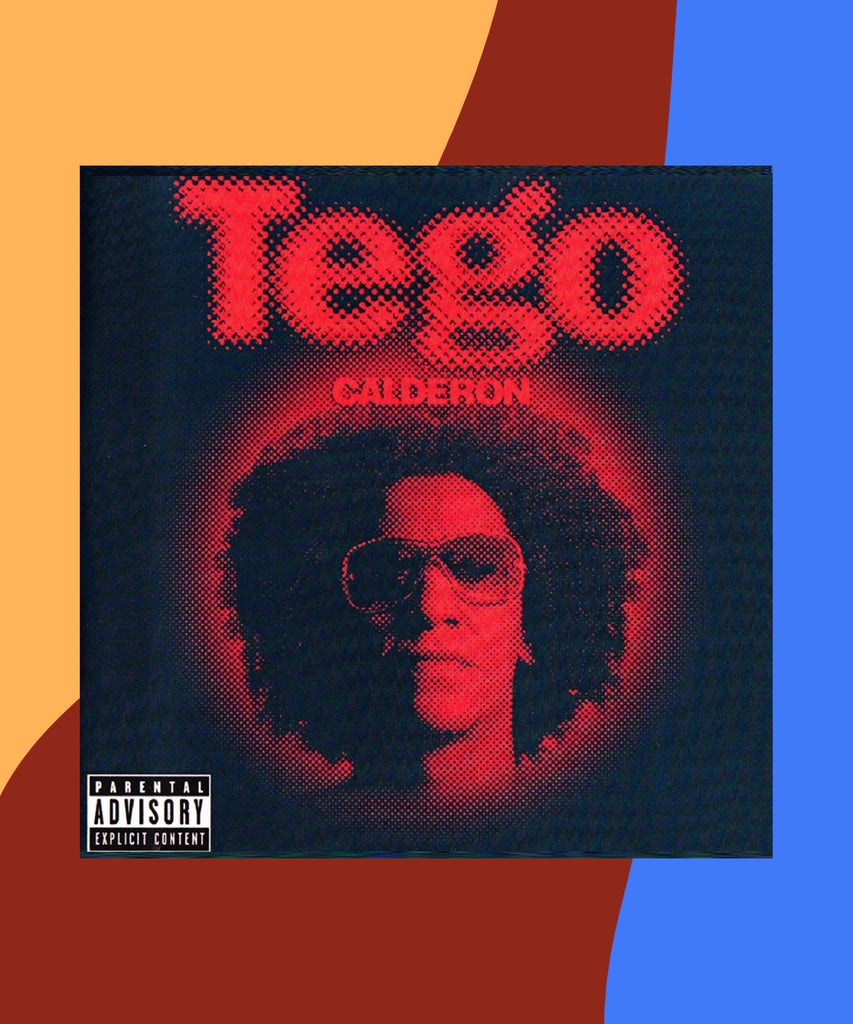

The 2000s reggaeton explosion saw the progressive “sanitation,” or white-washing, of the genre, which was previously spearheaded by hugely popular acts like Wisin y Yandel and Los Bambinos. Tego’s El Abayarde dropped in timely fashion and emerged an affront to the assimilation of styles more palatable to his white peers and audiences. El Abayarde, whose cover art boasts the iconic red-and-black image of an afro’d Tego, is produced by a bevy of beat maestros that include DJ Nelson, Luny Tunes, and Noriega. Each record is a dedication to Puerto Rico’s folkloric identity, with Tego pioneering the use of splicing reggaeton with Puerto Rican bomba and Cuban guaguancó, in addition to Dominican dembow, Jamaican reggae, and several other Afro-Caribbean sounds. “I started to make music from a Black beat, so that Black people can feel proud of being Black,” he told NPR in a conversation about growing up in a pro-independence household back in 2008.

“Before Daddy Yankee became the poster child for radio reggaeton and Don Omar the king of reggaeton romantico, it was el Negro Calde’s socially conscious and hip-hop storytelling that carried the bubbling genre into the mainstream and across international borders.”

Marjua estevez

While reggaeton subject matters are infamously associated with violence and misogyny, Afro-Boricua artists like Tego characterized his style early on with lyrics against corruption and racism in the Puerto Rican government. Songs like “Dominicana” explore themes of immigration and the negotiations of marriage between the neighboring islands of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. On “Loíza,” he sings praises to the people that produced him and gives the proverbial middle finger to Spain, who colonized the archipelago following the invasion of Christopher Columbus. “Si una buena madre sus hijos no dañan; cabrones, lambones pal carajo España,” he said, marking the first time I ever heard a Spanish-speaking Caribbean rapper so enthusiastically denounce the Eurocentricity associated with Puerto Rico’s alleged “tres razas” heritage.

Modern use of “Afro-Latinidad,” though hardly new, was not mainstream jargon in the early 2000s. Yet part of what separates Calderón from his Afro-Latine contemporaries, like Ivy Queen, Don Omar, and Zion y Lennox, was the unwavering ambition behind centering his negritude. One could argue Tego put his Blackness even before his ethnicity, a concept many Black Latines contend with daily as Latine identity is more and more obscured in the face of present-day social decolonization. Calderón’s radical approach to reggaeton and the deliberate ways in which he chose to use his platform inarguably paved the way for artists like Bad Bunny, who is today heralded for shattering gender norms and protesting against the Puerto Rican government.

Calderón also laid a blueprint for “crossing over.” One of the first reggaeton and Spanish-language hip-hop artists to foray into popular culture, Tego not only gained respect commercially in Puerto Rico and the States, but he earned esteemed co-signs from North American hip-hop figures. Despite not speaking or rapping in English, top names like N.O.R.E, Lil Kim, Fat Joe, and 50 Cent were eager to work with him because they recognized that Calderón was changing the game. In the spring of 2005, he signed a joint deal with Atlantic Records and his own Jiggiri Records, becoming the first reggaeton act to ink a global distribution deal with a major record label — without watering down his roots.

Two decades later, El Abayarde is a firmly established multi-prong attack on the status quo in that in one fell swoop Tego celebrated women’s autonomy and sexuality, threw down a lyrical gauntlet in hip-hop, and gave the world brilliant context about the Black Puerto Rican experience. El Abayarde sold more than 350,000 copies worldwide without major label backing and was nominated for a Latin Grammy Award. It also made him one of the most successful tour acts in urbano history. “Desde la cuna, agradecido de esta negrura,” he spits on the title track, giving thanks for his Blackness in an industry that historically neglects it.

In honor of the relentless stinging ant out of the West Indies — the inspiration behind his debut album — Black women writers, educators, and artists from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic author heartfelt words about El Negro and the album that vindicated so many of our hoods and caserios.

Venessa Marco, Writer & Educator, Santurce, Puerto Rico

Tego Calderón’s El Abayarde put so many parts of our culture at the forefront: our Blackness, our style, our slang, and even our love for other genres. He is one of the first artists that I can think of in reggaeton who incorporated guaguancó, timba, son, salsa, and merengue. You can’t listen to a song on El Abayarde and not get lost in the percussion. We’re talking about someone who dances conga, someone who talks about being hijo de Obatala, who uses every aspect of what it is to be of African heritage, what it is to be Black, to be seen.

Part of why his impact has been so profound and why he completely shifted reggaeton, for me and many other Black and Brown Puerto Ricans, is because he made it evident that there are so many of us out here and that our roots are intact. I don’t want to use the phrase “unapologetically Black” because there is no connotation of regret; that’s what I think was so different about Tego. It wasn’t boldness, unapologetic behavior. It was, “This is who the fuck I’ve always been. This is how I was raised. This is where I’m from. This is what being Black means, and everyone around me is also this” instead of “I’m the one who is different here and I’m the one who is going to make you respect me for that.” Tego made it clear that the spectator was being invited into our world. El Abayarde was not just a showcasing of that world, but a statement on how this has always been our world. It was a statement about reggaeton being Black; how it’s always been Black and will remain Black. That’s how he presented himself and how he approached his work.

“Tego Calderón’s El Abayarde put so many parts of our culture at the forefront: our Blackness, our style, our slang, and even our love for other genres.”

Venessa Marco

He wasn’t the only Black Puerto Rican coming up or who made a name for themselves, but Tego is someone who put his Blackness first and his artistry came after. We didn’t see that before Tego; and with this album, we saw how desperately we needed that. It was beautiful to have that kind of representation and visibility then and now, especially with the ongoing white-washing that still occurs in Black genres like reggaeton today.

He spans generations, too. The people who critique reggaeton and those who listen to it — in Puerto Rico, we call reggaeton heads “cacos” — they tip their hats off to Tego because he understood and spoke their language and purpose. He was familial. He was our uncle telling us what it was and what it is. He wasn’t only telling us how beautiful it is to be Black and Puerto Rican, but also rapping about the state of Puerto Rico. Tego is someone who talked about colonialism and imperialism very early on, and I would argue he is actually one of the first people I ever heard refer to the States as el imperio.

Tego’s legacy — his personhood and his artistry — is beyond anyone else’s for me. I associate him with my Blackness, my childhood, my roots, and the craft. People reduce reggaeton’s importance and they love to suggest that it isn’t music. But then you listen to songs like Tego’s and albums like El Abayarde, and they completely shatter such trivial thinking.

Xiomara “DJ Bembona” Henry, Brooklyn, New York

El Abayarde stands for Blackness throughout Latin America, but especially throughout the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. There wasn’t anything that represented us in that way at that time. Twenty years later, El Abayarde resonates with me even more. I was 12 years old when the album dropped. As a young Black Boricua from Brooklyn, I had a lack of understanding about colorism, about the ways racism shows up in our lives, and of my own identity. Because I stand firm in who I am and where I come from today, Tego’s El Abayarde means that much more to me in a political climate seething with anti-Black and anti-immigrant rhetoric. The songs on that album touched on so many things, everything from negritude to colonialism to female autonomy.

Forget simply calling this a reggaeton album. This album is Black as fuck, and it’s hip-hop as fuck. It’s an album brimming with negrura and what it means to enthusiastically stand in your own skin as a Black caribeño and a Black Puerto Rican. Tego quite frankly didn’t give a fuck about white people, or at least the white gaze. And that’s in part why El Abayarde is in a league of its own even two decades later. The musicality alone is proof that Tego’s ears were as prolific as his voice. He was very intentional about employing DJ Nelson and Noriega and all the others. We hear jazz samples, orchestral elements, Dominican and Jamaican rhythms, and bomba de la pura from Loíza. Musically, the project for me is one of the earlier, more cohesive body of reggaeton works created in the studio. Not only is he possessed of a distinct voice, but how he puts words together is nothing short of magical. He’s an MC, through and through.

“It’s an album brimming with negrura and what it means to enthusiastically stand in your own skin as a Black caribeño and a Black Puerto Rican.”

DJ Bembona

Tego in the end brought with him our chants, our history, and our power. Never before this moment or album, in the movement of reggaeton as it was on the cusp of something far bigger, did we have someone like Tego kick in the door from the underground. El Abayarde represents so much of the Black diaspora, of what it means to so intentionally celebrate one’s negrura, irrespective of language or geographical location.

Monique “DJ Agent DMZ” Suarez, Salinas, Puerto Rico

I’ll never forget how I felt when I first saw El Abayarde’s cover art. Seeing this Black man from Puerto Rico rocking his big ass ‘fro, it did something to me. It wasn’t just some stock image. This was a real Black Boricua artist, all up in our faces, on the cover of a reggaeton album that was about to change the game forever.

Growing up in Puerto Rico, we didn’t see a lot of Black people on television. I can’t even tell you what artists were on TV growing up that were Black and I could look up to. Tego’s presence and introduction helped me realize the gravity of seeing people who look like you in media, in music, and in the arts. It’s factors like these that can ultimately shape you and influence how you love yourself as a Black child.

I was living in Orlando when El Abayarde came out. That album helped me keep my Puerto Rican-ness at a time when I was being uprooted from my home back in Salinas. There was a lot of rock, punk, and alternative music happening around me in Florida. Tego really kept me grounded. Even though we don’t talk enough about the fact that Tego was first a rockero before he got into rap, it’s albums like El Abayarde that soundtracked my youth and helped me stay connected to my original home. He opened the doors for so many of us Black Boricuas, and his debut album gave the world so much gorgeous and necessary context about who we have always been.

“With El Abayarde, Tego centered the soul of reggaeton.”

DJ Agent DMZ

Tego kicked in the door with his narrative, with my narrative, and he did it without watering it down. He didn’t pull back his hair. He didn’t fix his mouth. He didn’t whiten anything about himself or his work and purpose. El Abayarde is a reflection of Afro-Puerto Ricans all around the archipelago, not just San Juan, and across the diaspora. It sonically props up all of the things we know and love about being Puerto Rican. His music was radical in the way he incorporated traditional bomba, which I don’t think a lot of reggaeton artists really know how to do. With El Abayarde, Tego centered the soul of reggaeton.

Ser Álida, MFA Candidate in Fiction, University of Mississippi

When Tego Calderón arrived, he reintroduced craft without compromising el sandungueo y el bellaqueo, giving lyricism in reggaeton — a genre with tethers in Black Panamanian reggae and U.S. hip-hop — a proper homecoming. El Abayarde is an album made in response to a lot of social or cultural criticism. If we go through the songs, a lot of them are tiradera songs, songs from the mixtape that made it to the biggest-selling reggaeton album that it was. His use of language and politics, in so many ways, resurrected the greats of his day. By challenging them lyrically on this album, Tego moved artists like Lito y Polaco to pick up the mic again.

At the height of it, reggaeton encouraged sex and sexuality, but there was often no context for it. There was no context to all this sexual freedom and what that could mean and look like. Tego Calderón was revolutionary in that he understood that we wanted to fuck and that we wanted to party, but that there was a way to do it — because we are also dying. They are also killing us. There are also a number of things happening as part of Black people’s daily lived experiences. Songs like “Al Natural” and “Pa’ Que Retozen” offer context on safe sex. Tego is saying go have fun and fuck, but protect yourself. Do it safely. This is critical social commentary. He’s talking about condoms. Ain’t no rapper coming up then and even now talking about safe sex.

“El Abayarde, at the end of the day, is hip-hop.”

Ser Álida

Not only did he come out the gate celebrating Blackness in the Caribbean and Latin America in new ways, ways that I as a Dominican hadn’t seen before, but his lyrics also celebrated women’s sexuality in ways reggaeton typically failed to do. His approach to sex and sexual autonomy was different from popular reggaeton. It was maldita puta this, maldita bellaca that, which we love and need, but Tego’s appreciation of the woman’s body was almost a celebration. That, for me as a teen, was super empowering.

El Abayarde, which means fire ant or stinging ant, had no fear in its lyrics or delivery. There was no ambiguity in his Blackness or who he is in totality. The album introduces talking points about the things happening in Loíza, in the greater island of Puerto Rico, that we still see today. What’s more, I would argue that Tego and his debut paved the way for what Dominican rap came to be. It gave Monkey Black and El Lapiz the permission, so to speak, to do the same with their language and politics. El Lapiz wouldn’t be who he is if that album hadn’t dropped. That album made a lot of statements. Before Tego, rappers weren’t really fucking with reggaeton like that. Tego changed that shit, because El Abayarde, at the end of the day, is hip-hop.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

from Refinery29 https://ift.tt/oG4DCaK

via IFTTT